Superman, Batman, and the Evolution of the ‘Perfect’ Hero Body

Over the last 60 years, on-screen superheroes have reflected America’s changing ideals for men’s physiques.

Every spring and summer, one thing moviegoers can reliably count on is a bumper crop of comic-book movies. At this point in time, studios have run through the A-list (Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, The Hulk), hit the B-list (Iron Man, Thor, Daredevil), and are now chugging through the C-list (sorry, Ant-Man, Deadpool, Guardians of the Galaxy et al).

Another unavoidable fact is that these movies will feature actors who undertook rigorous diet and exercise regimens in preparation for their spandex suits. The ritual of actors bulking up or shedding fat for their superhuman roles may feel inevitable now, but the current standard for impossibly brawny comic-book heroes is something of a new development. Over the past few decades, there’s been a substantial amount of fluctuation when it comes to portraying the “perfect” male body. As an infographic published by The Economist reveals, Adam West’s Bruce Wayne, weighing in around 200 lbs, might surprise viewers familiar with Michael Keaton’s Caped Crusader (158 lbs), while both heroes would be dwarfed by Ben Affleck’s Batman (216 lbs and 6’ 4”).

In fact, the changing bodies of Superman, Batman, and other superheroes of the DC and Marvel universes illuminate the ways the ideal male physique has evolved in American pop culture over the decades.

* * *

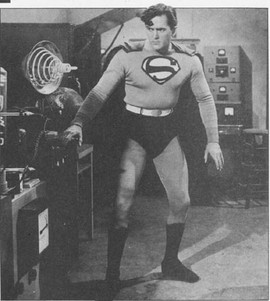

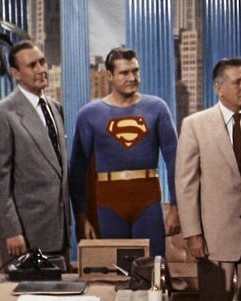

In the ’50s and ’60s, the film and television industries began their love affair with men in capes. Though these heroes stopped locomotives, jumped over buildings, and retreated to secret lairs, they didn’t have quite the same look (massive shoulders, V-shaped torsos, and rippling abs) as today’s superheroes. Kirk Alyn, the first actor to play Superman in 1948, looked more like a college athlete than an alien Adonis. Later the role was taken over by George Reeves, the quintessential ’50s Man of Steel. Reeves was a broad, barrel-chested hero with a square torso, long limbs, and barely a muscle in sight. But he had a John Wayne-esque brand of masculinity—solid, stable, and strong-jawed—that made him compatible with the times.

In 1966, Adam West took on the role of Batman in the eponymous TV series. West’s runner’s build was sturdy, and out of costume, his Bruce Wayne looked more like James Bond than Charles Atlas. (Incidentally, West was tapped for the role after he played a Bond-inspired spy in a Nestle Quik commercial.) Unlike later Batmans, West didn’t physically transform when he donned his batsuit, morphing from Bruce Wayne to the otherworldly Batman. His simple gray and black outfit only heightened how ordinary his physique was for a man regularly tasked with saving an entire city. West later joked about his appearance on the show when he made a cameo appearance on The Simpsons, saying, “Back in my day, we didn’t need molded bodysuits, [it was just] pure West.”

At that time, Hollywood hadn’t yet discovered skin-tight Lycra or molded plastic pectorals, so costumes were mostly full-body stocking knits. Overall, they revealed little to no hint of the muscles below, highlighting that the physical image of these superheroes was much closer to that of their viewers. In the early 1960s, adult men had an average BMI of about 25, which sits in the “normal” range—a healthy mix of muscle and fat. (Curiously, the average American man today, in the age of uber-buff superheroes, has a BMI of 29, according to the CDC.)

* * *

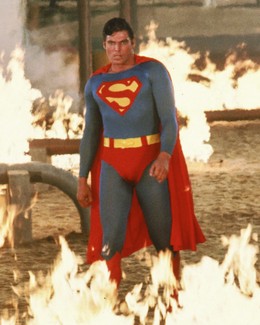

Christopher Reeve as Superman in 1983 (Warner Bros.)

By the late ’70s and ’80s, synthetics were booming. Spandex, polyester, and Lycra, which were invented in the late ’50s, had been refined, and had found new popularity in the disco era. With these materials in high supply, supersuits finally started using stretchy material—a development that would lead to an emphasis on heightened fitness. It was during this time that Christopher Reeve was tapped to become the new Superman. Producers, concerned by Reeve’s naturally tall and slender frame, pressured him to wear fake muscles under his suit. He refused, instead becoming an early adopter of a now-familiar routine: He hired a trainer and put on 30 pounds of muscle. Reeve couldn’t change his bone structure, but he managed to gain biceps, strong shoulders, and the outline of abdominals, all of which were accentuated by his skin-tight outfits. Reeve’s Superman represents a male ideal shaped by the ’80s jogging craze and Jane Fonda’s VHS aerobics.

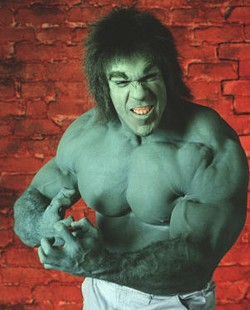

In 1978, The Hulk grimaced and flexed his way onto TV screens. Lou Ferrigno’s Hulk resembled a Greco-Roman wrestler, with popping veins and enormous muscles. Unlike other actors who’d played superheroes in the past, Ferrigno came from a bodybuilding background. These two points, Reeve to Ferrigno, represent a limited range of hyper-fit masculine bodies—but it’s still a wider variety than viewers see in many superheroes today. As the Olympics frequently remind audiences, two bodies in peak physical condition can look very different—but it’s a fact Hollywood doesn’t acknowledge much anymore.

* * *

In 1991, a new, alternative rock-influenced aesthetic began to break out from Seattle’s street culture. Nose rings, neon hair, and flannel moved from the fringes into the mainstream, and in the middle of this, Kurt Cobain epitomized a new masculine prototype. “[He] was the antithesis of the macho American man … he made it cooler to look slouchy and loose, no matter if you were a boy or a girl,” said The Fader’s Alex Frank to Vogue. This asexual look was softer and influenced by the same “heroin chic” look that glorified waif-like appearances in women.

The superhero world saw its own alternative figure emerge when, in the mid-’90s, Brandon Lee brought the dark, brooding figure of The Crow to movie theaters. He looked almost like a strung-out Batman, gothic and lanky with pale skin and messy hair. The movie was a box-office sleeper hit that went on to spark a sequel (despite the tragic death of its lead actor before filming even wrapped). Around the same time, the comic-book character The Sandman, also known as Dream, appeared in an ongoing Vertigo series—he, too, had a skinny-rocker look closer to Sid Vicious than to Superman. (The film version of this character got lost in development having bounced around between various producers and writers. A scathing review of the working script on Ain’t It Cool News in 1998 essentially killed the project.)

In this kind of cultural environment, the muscled heroes of yesteryear started to become objects of comedy or even straight-out mockery. It was this decade that presented Batman & Robin, the most lighthearted and campy of all the movies in the DC franchise. Batman and Robin were also explicitly sexualized in that film, with superhero suits that sported nipples and repeated shots of codpieces and bat buttocks that intensified the comic effect. It was also midway through the ’90s that the popular animated show Ren and Stimpy introduced Powdered Toast Man, a baritone-voiced superhero with gleaming butt cheeks whose tagline to people he rescued was, “Cling tenaciously to my buttocks!”

But with the new millennium a kind of truce formed, and a variety of bodies began to be represented. Perhaps no movie represents this better than 2009’s Watchmen. The ensemble here included the ultra-muscled Dr. Manhattan—who sported a computer-generated body modeled after that of the fitness guru Greg Plitt—and the middle-aged Nite Owl, who wore a sculpted outfit that hid his otherwise out-of-shape figure. It’s worth mentioning that neither man is an object of ridicule, and both are love interests for Watchmen’s leading lady. They share the role of protagonist and both claim the audience’s compassion and respect, signaling an increased acceptance that men of all shapes and sizes can be romantic heroes.

As for this current decade, superhero stories are like Dr. Octopus’s tentacles, stretching into every direction with multiple spinoffs. But it seems that as studios continue to roll out more superheroes, the leading men are becoming homogenized. Captain America (Chris Evans), Iron Man (Robert Downey Jr.), and pretty much the entire Avenger’s lineup is a fleet of cookie-cutter musclemen. Even when “schlubby” (or snarky) antiheroes appear like Deadpool (Ryan Reynolds) or Peter Quill in Guardians of the Galaxy (Chris Pratt), they still come with an action-ready six-pack. Meanwhile, characters with other body types are often alien or not human at all, as is the case with Peter’s raccoon sidekick.

The same seems to have held true for Batman v Superman and the upcoming Captain America: Civil War, X-Men Apocalypse, Wolverine, and Guardians of the Galaxy’s sequel. These superheroes are approaching a point of such rigid physical perfection that Hollywood is hovering dangerously close to the uncanny valley, a place of eerie, manufactured humanity. As this ideal becomes duplicated ad nauseam, it might end up disconnecting with viewers—because this echo chamber of muscle men neglects what’s actually compelling about superheroes: the place where “super” and “human” intersect.

Of course moviegoers still expect their superheroes will be better, stronger, and closer to god-like than the average man. But the superheroes of the previous decades could convey superiority along with a dose of humanity. After all, there’s no true heroism without a degree of vulnerability. Even the early radio programs of Superman understood this—that’s why they invented Kryptonite.