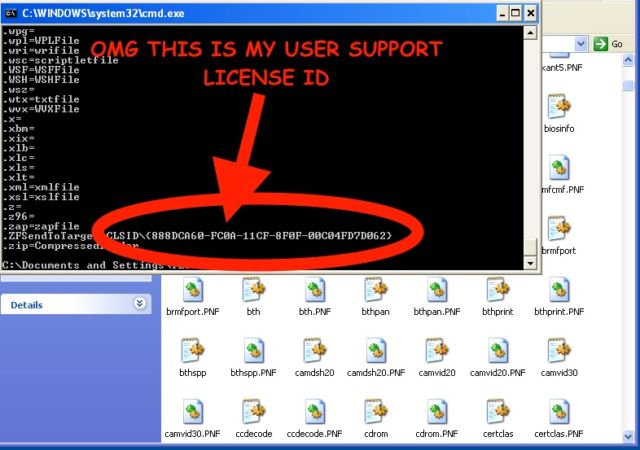

Technical support scams are the bottom of the barrel for cyber-crime. Using well-worn social engineering techniques that generally only work on the least sophisticated computer users, these bootleg call-center operations use a collection of commercially available tools to either convince their victims to pay exorbitant fees for "security software" or extort them to gain control of their computer. And yet, these schemes continue to rake in cash for scammers.

We've dealt with these scammers before at Ars, but this week I got an opportunity to personally engage with a scam operation—so naturally, I attempted to inflict as much damage on it as possible.

On Monday afternoon, I got a phone call that someone now probably wishes they never made. Caller ID said the call was coming from "MDU Resources," but the caller said he was calling from "the technical support center." He informed me there were "junk files" on my computer slowing it down and that he was going to connect me with a technician to help fix the problem.

I was thrilled, displaying what my wife Paula felt was an inordinate amount of glee about getting the call. Over the next two hours, I subjected the scammers to such misery that Paula later told me she felt bad for them. "They probably had a quota to meet," she said sarcastically. "You probably kept them from getting four or five other people."

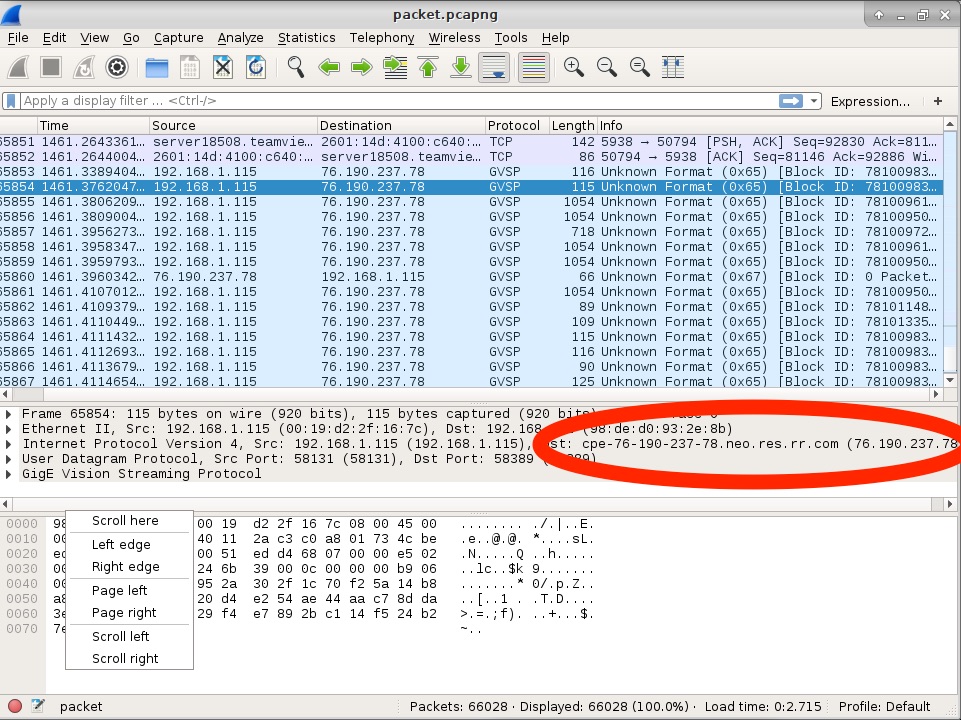

Actually, with any luck, I did more than that—I passed on the data I collected to the operators of the infrastructure used by the scam. That should at least put a speed bump in this particular nefarious operation. But taking down a scam like this is akin to a game of whack-a-mole; the infrastructure they use is too easily replicated. It's simple for support scammers to mount call center campaigns from cheap (or even stolen) VoIP services. Many of the tools they use offer free trials that can be repeatedly abused. And there's so much money in fooling naïve computer users that scammers are motivated to do this again and again. The FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) reported last June that just in the first four months of 2016, the bureau "received 3,668 complaints [of technical support scams] with adjusted losses of $2,268,982."

Loading comments...

Loading comments...